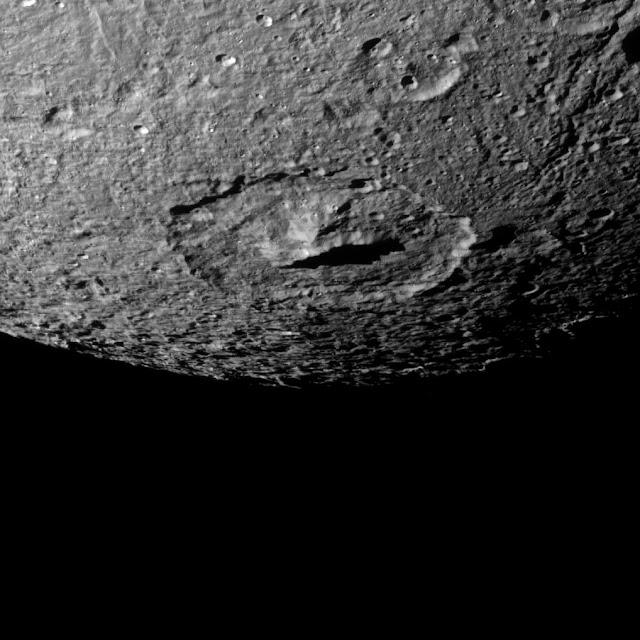

The Cassini spacecraft captured this high-resolution view of the cratered surface of Saturn's moon Rhea as the spacecraft flew by the moon on October 17, 2010.

For closer views of Rhea's surface from earlier flybys, see PIA07765 and PIA08402. This view is centered on terrain at 60 degrees North latitude, 251 degrees West longitude on Rhea (1,528 kilometers, 949 miles across).

The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft's narrow-angle camera. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) from Rhea and at a Sun-Rhea-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 88 degrees. Image scale is 238 meters (781 feet) per pixel.

Photo credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute